CLICK TO SHOP OUR BLACK FRIDAY SALE!

*Excludes BioNude and subscriptions

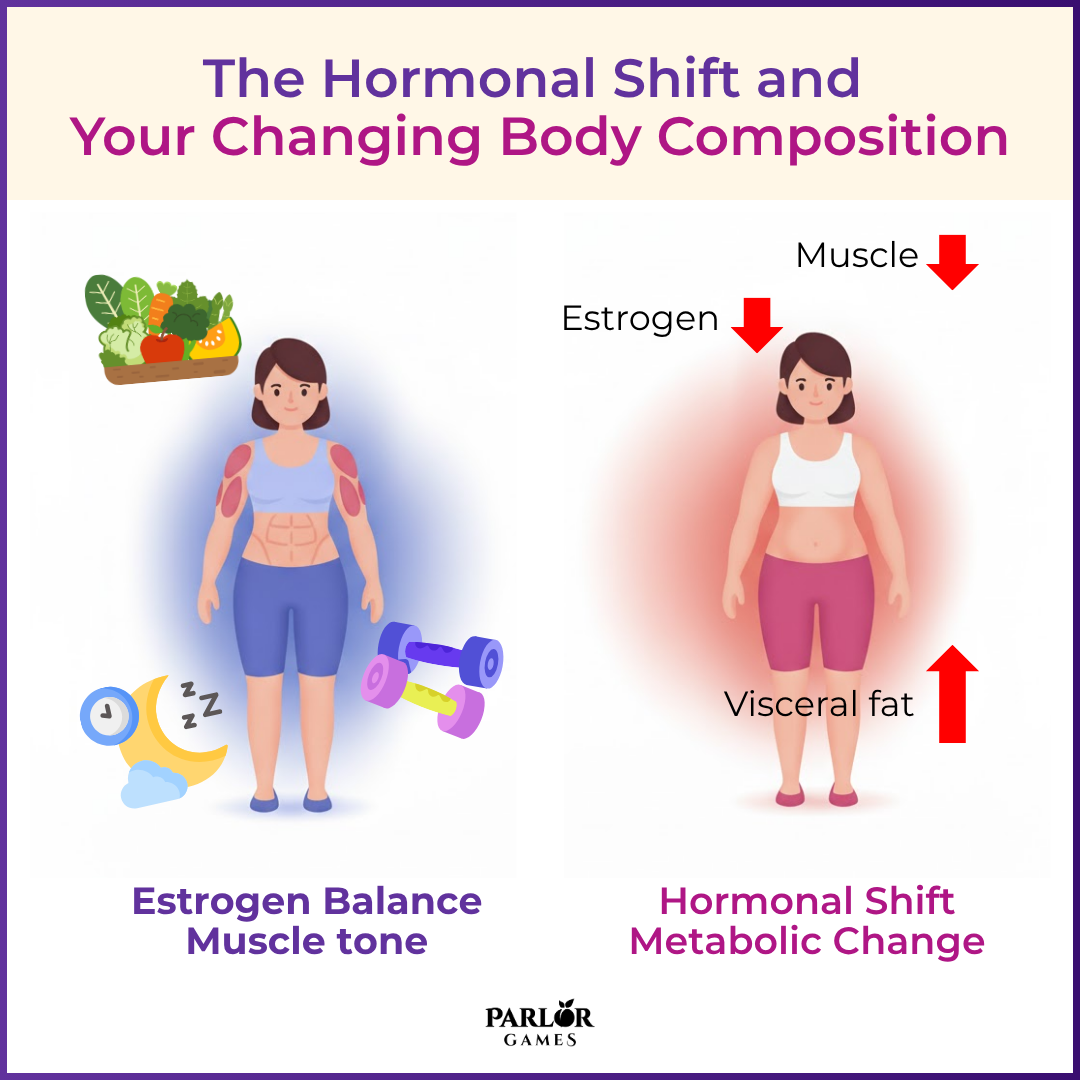

Menopause commonly shifts body composition toward more abdominal fat and less muscle - changes that increase cardiometabolic risk - and the best current strategy is resistance training, good sleep and nutrition, daily movement, plus individualized clinical options (including menopausal hormone therapy) when appropriate. In this narrative review, Anna Fenton summarized research about how weight, body shape, and body composition change during the menopause transition, discussed likely biological and lifestyle drivers, explored health consequences, and outlined management strategies.

Menopause commonly shifts body composition toward more abdominal fat and less muscle — changes that increase cardiometabolic risk — and the best current strategy is resistance training, good sleep and nutrition, daily movement, plus individualized clinical options (including menopausal hormone therapy) when appropriate.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Disclaimer: The information provided above is intended for educational and informational purposes only. Statements made have not been evaluated by the FDA nor are they intended to treat or diagnose. Any health concerns should be discussed and evaluated by your primary health care provider.

Parlor Games, LLC ● kate@parlor-games.com ● 5304 River Rd N Ste B ● Keizer OR 97303

Disclaimer: The information provided above is intended for educational and informational purposes only. Statements made have not been evaluated by the FDA nor are they intended to treat or diagnose. Any health concerns should be discussed and evaluated by your primary health care provider.

28 Day Challenge Subscription Details

We ship you a 28 day supply of Silky Peach Cream for only $29 (more than 25% off our normal price) when you sign up for Subscribe & Save.

Follow the directions we include in the package and apply Silky Peach cream on your tender bits for 28 days.

Decision Day:

5 days before your subscription rebills, we’ll send you an email reminder with a link. If you decide Silky Peach is nice but not your thing… you can click that link and cancel your subscription without even talking to anyone. No hassle — no questions asked.

If you are like 72% of our Silky Peach customers, you’ll love it and can't imagine life without it. In that case, do nothing, and we’ll welcome you to the Parlor Games family and ship Silky Peach Cream to your door step every month for the same discounted price of $29 — locked in for as long as you remain a subscriber.

Important note about our easy-breezy subscriptions:

We know that some companies make it hard to cancel a subscription — that’s not us. Our mission is to save the world — one vagina at a time! If you decide you don’t need Estriol as an ongoing solution for dryness, incontinence, UTIs and keeping sex fun and comfortable again, we understand. Five days before we ship your next order, you'll receive an email with a link to cancel right there in the message.

No hunting, no searching, we got you. Respect is where it’s at.

FYI – Estriol is beneficial for skin integrity and mucous membranes. It’s great for vaginal atrophy and also amazing for use on the face and neck. Applying a small amount — about 1 pump — can help build the collagen and plump up the cells to reduce wrinkles. Who knew!!

OUR HAPPINESS GUARANTEE

We want you to feel safe and confident trying any of our products. That's why we promise 100% money-back guarantee on the purchase price of the first bottle of any of our products. Balancing hormones DOES take some time, so please try it for 28 days. If after 28 days you are unhappy, or the product just hasn't worked for you, simply contact us and we'll process a refund of your full purchase price upon receipt. Sorry, shipping fees are not refundable.